Iconography as text

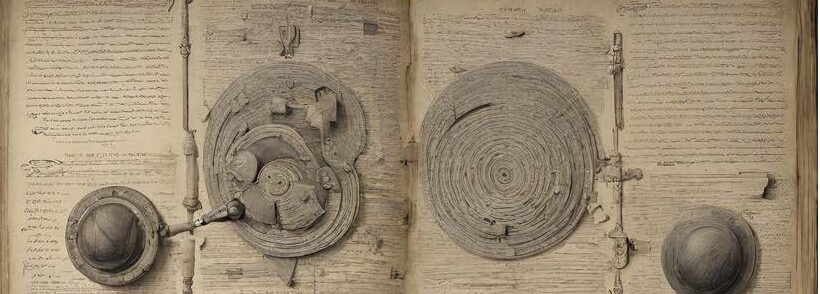

As far back as civilization takes us, humans have always been working out and creating different ways to communicate, to represent their soulful being to others and record their existence through times and to the next beholders. In light of their well sought approaches, humans have gotten creative and more diverse in their means of communication. What makes art special is its repetitive use across various civilizations, and what makes iconography special in particular is its own nature. Iconography comes from the Greek word “ikon” meaning image, and a big difference between words and images in communication is the borderlines of the written language (words) (Marquez, 2022). On the other hand, images or more specifically iconography proved to be universal in conveying all sorts of messages and has no limitations or barriers like words do. Moreover, the purpose remains similar as they are both a media of communication. Which ultimately establishes the fact that iconography is text (Treharne & Willan, 2019). Therefore, Iconography in particular will be the focus here as its own medium of communication.

Iconography can be viewed as a range of symbols or paintings that has been widely used for centuries across different regions and civilizations. Even though the written language existed through these civilizations (Egyptian hieroglyphics, archaic Greek for Byzantines), they came up with and developed Iconography to convey different kinds of messages, using it as a separate medium of communication. In a similar way in which different media are used in different contexts (not everything written is said and vice versa). Furthermore, Iconography has been developed by different churches and rulers along with artists for the sole purpose of delivering a specific message across different periods of time (Marquez, 2022). A good example would be a painting that depicts Mary the virgin which was done in the 12th century to commemorate the figure while also serving as a symbol of Christianization, and centuries later, people are still amazed by it and perceive it as it was meant. The significance doesn’t stop at the skillful painting, but to capture a message in a way that can be interpreted by anyone, anywhere, and anytime.

Evidently, Iconography has proved to communicate these messages or beliefs in a longer lasting fashion as they tend to directly emphasize a certain idea into a painting.

Even though iconography has been heavily associated with religion and specifically the catholic church with Saint Luke the evangelist being the first iconographer. Historical discoveries show us that it has been in practice since prehistoric times. In Egypt, Greece, Argentina and western Europe.

This shows us the universality of iconography as text, and it draws attention to further purposes. As mentioned above some distinctions of iconography, it not only brings people together in beliefs as it’s been known to play a big part in spreading Catholicism and maintaining it as a religion, but it also helps us to understand the motivation and intent behind it, a language of expressionism perhaps, while it could also play a role as an informative medium as its development in later times demonstrates.

Exemplary, the use of iconography in Greek mythology tells tales which have not been told in words, another good example would be The Lament for Icarus by Herbert Draper, which captures the final moments of an icon that symbolizes humans’ overreach for greatness and ambition as he attempted to fly to the sun only for his wings to melt, falling down into the sea and drowning would be his demise (Chaliakopoulos, 2021).

Such a story that could be interpreted broadly and philosophically wasn’t told in words, but rather a more interesting medium of text that goes deeper and engraves in history.

Finally, the more we look into it, iconography gets more fascinating as it carries symbolism heavily. In addition, as universal as it gets, it has its unique significance to different cultures. As text, it profoundly delivers meanings through depths uncovered by other media or means of communication.

References

Anthony, Jordan (2023, October 6th). What Is Iconography? – Learn About Iconography in Art

History.https://artfilemagazine.com/what-is-iconography/

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2014, February 4). iconography. Encyclopedia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/art/iconography

Cadario, M. (2014). Iconography in the Roman World. In: Smith, C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Global

Archaeology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_1472

Marquez, Valentina (2009, May 1). Iconography in Greek Mythology, Arcadia. https://www. byarcadia.org/post/iconography-in-greek-mythology-101-what-is-iconography

Meyer, I. (2022, 9 June). Famous Greek Paintings of Gods – The Best Greek Mythology Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-greek-paintings-of-gods/

Chaliakopoulos, A. (2021 September 6). The Myth of Daedalus and Icarus: Fly Between the Extremes. The Collector. https://www.thecollector.com/daedalus-and-icarus/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sandro_Botticelli_-_La_Primavera_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

https://sandrobotticellibelmonthonors.weebly.com/the-birth-of-venus.html

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cole_Thomas_The_Course_of_Empire_Destruction_1836.jpg

Nice.